TEE.fail:

Breaking Trusted Execution Environments via DDR5 Memory Bus Interposition

With the increasing popularity of remote computation like cloud computing, users are increasingly losing control over their data, uploading it to remote servers that they do not control. Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) aim to reduce this trust, offering users promises such as privacy and integrity of their data as well as correctness of computation. With the introduction of TEEs and Confidential Computing features to server hardware offered by Intel, AMD, and Nvidia, modern TEE implementations aim to provide hardware-backed integrity and confidentiality to entire virtual machines or GPUs, even when attackers have full control over the system's software, for example via root or hypervisor access. Over the past few years, TEEs have been used to execute confidential cryptocurrency transactions, train proprietary AI models, protect end-to-end encrypted chats, and more.

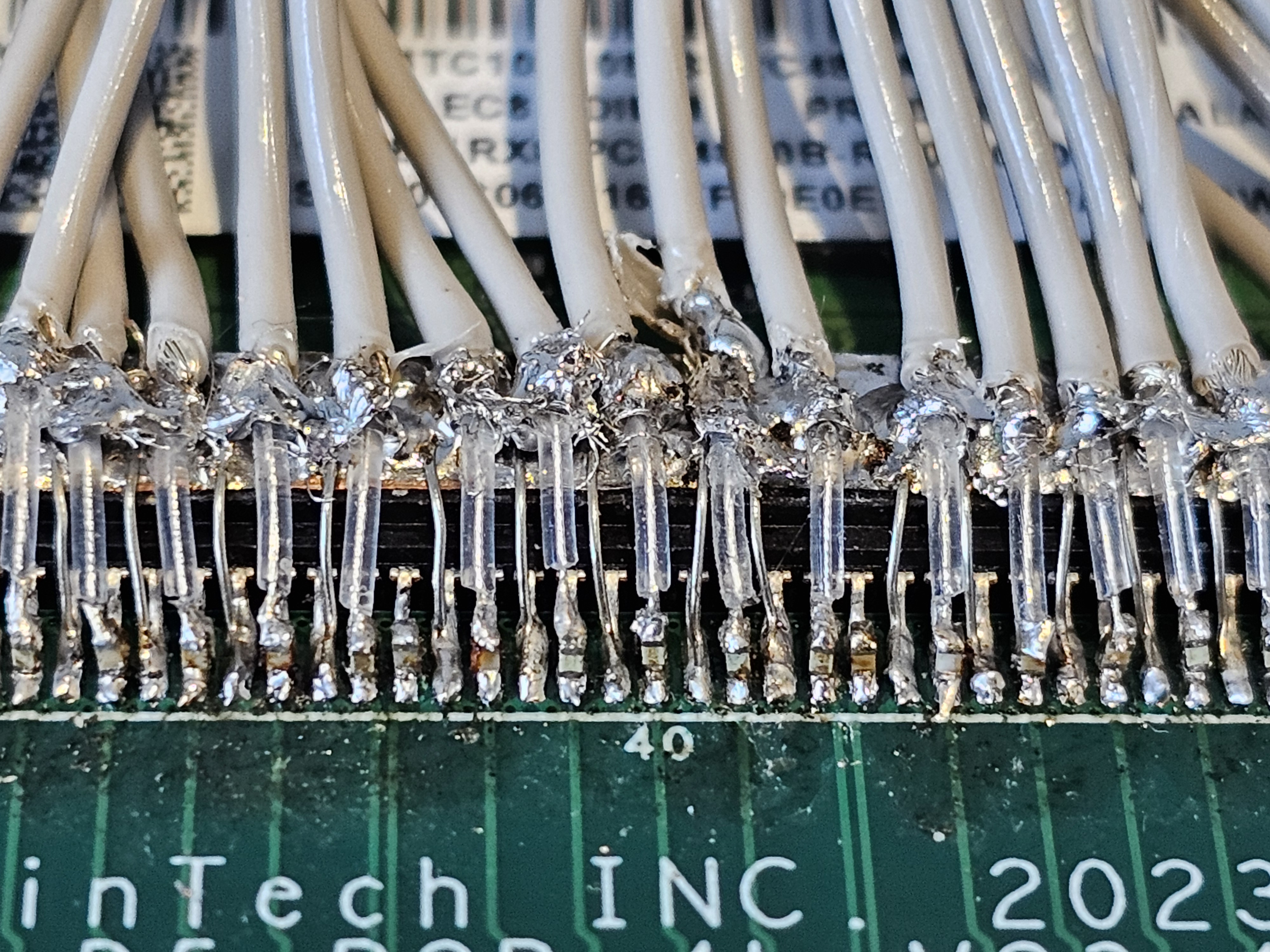

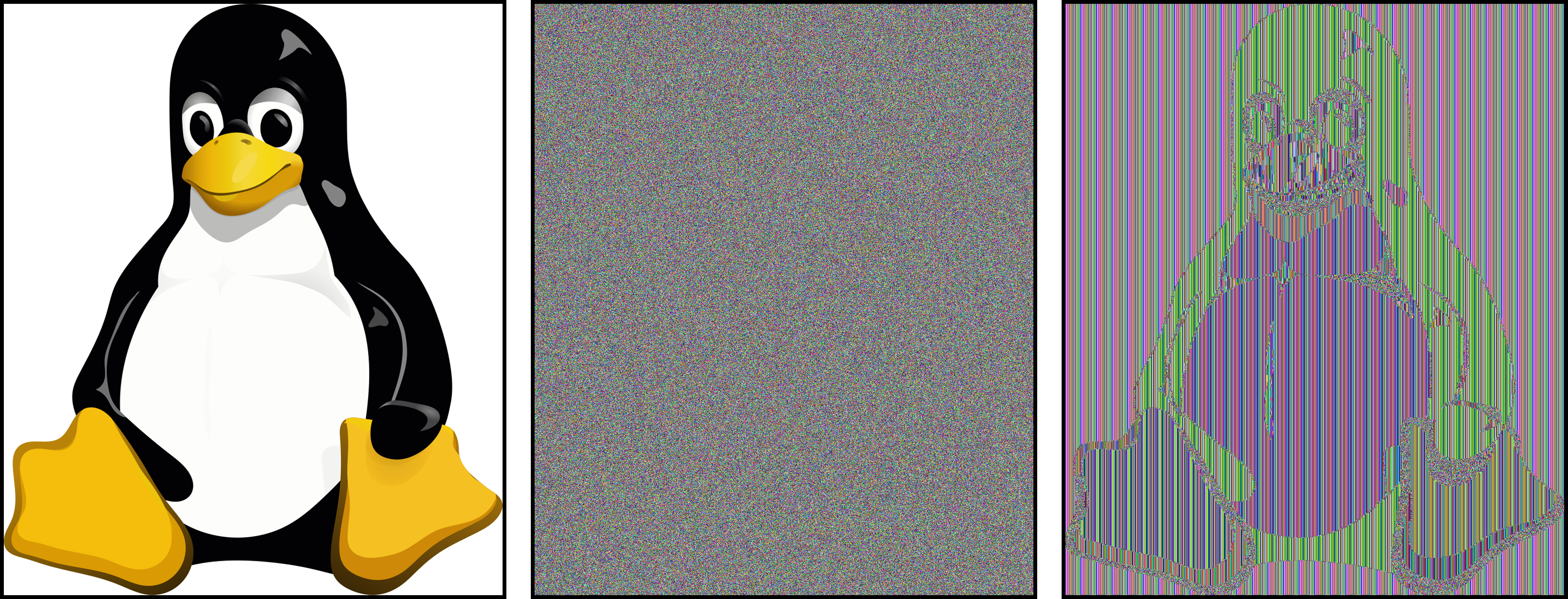

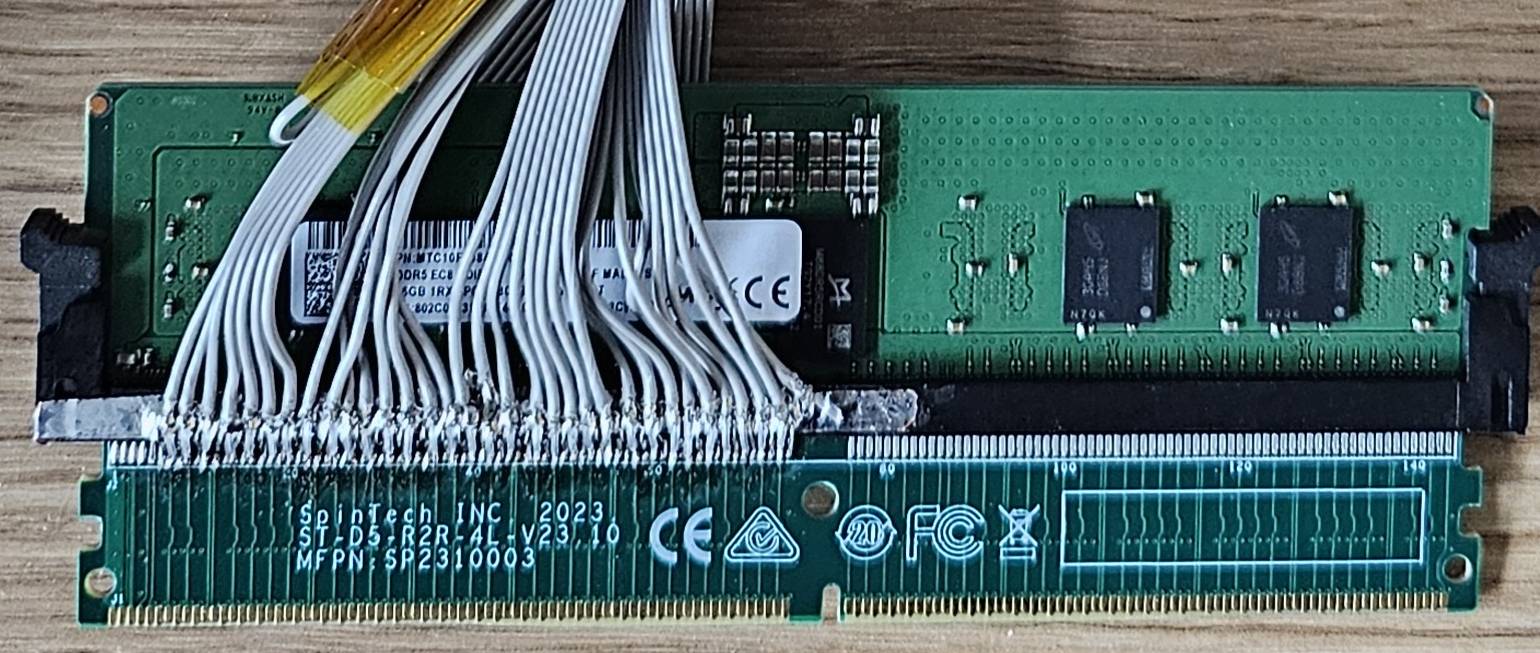

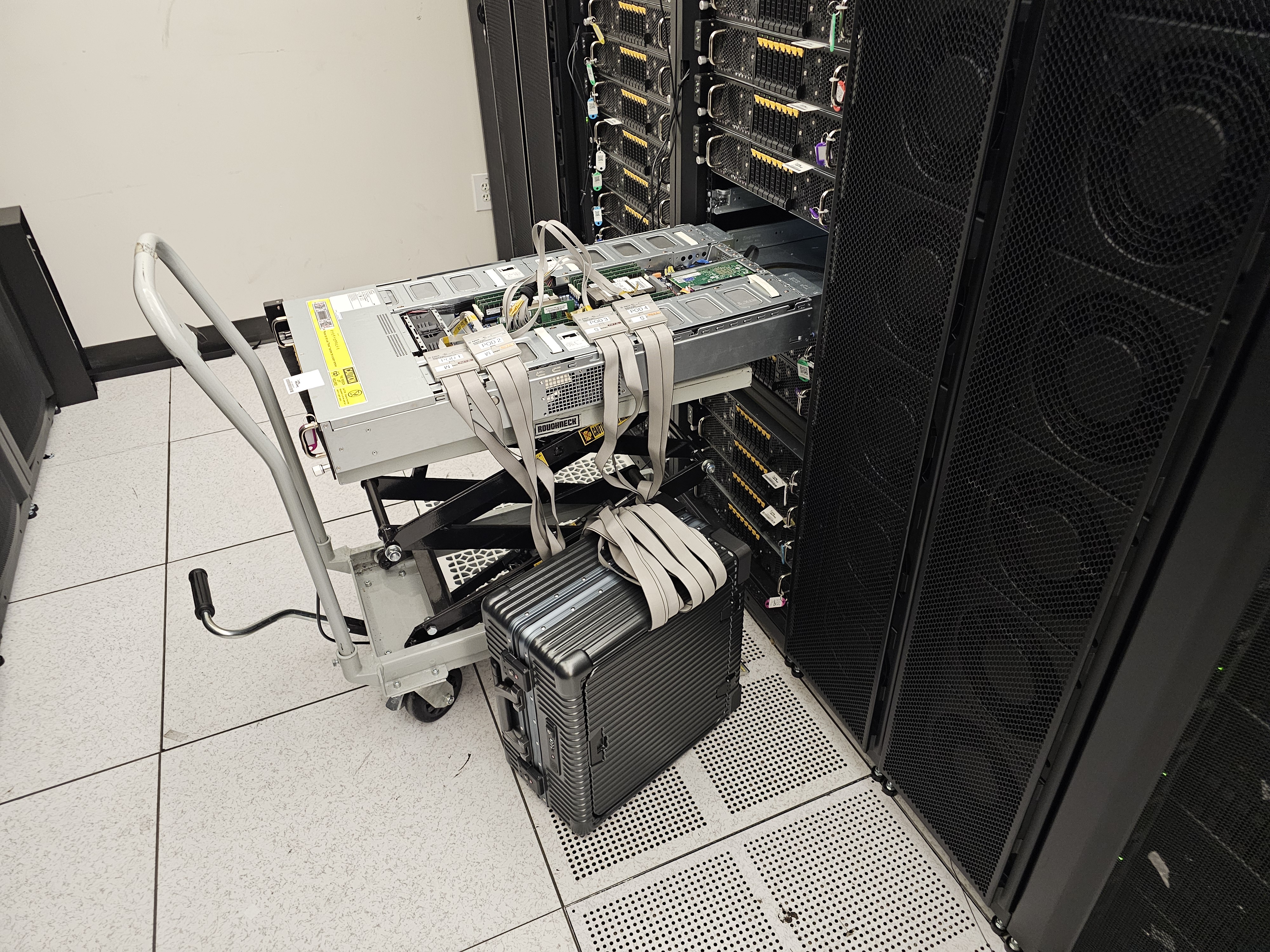

In this work, we show that the security guarantees of modern TEE offerings by Intel and AMD can be broken cheaply and easily, by building a memory interposition device that allows attackers to physically inspect all memory traffic inside a DDR5 server. Making this worse, despite the increased complexity and speed of DDR5 memory, we show how such an interposition device can be built cheaply and easily, using only off the shelf electronic equipment. This allows us for the first time to extract cryptographic keys from Intel TDX and AMD SEV-SNP with Ciphertext Hiding, including in some cases secret attestation keys from fully updated machines in trusted status. Beyond breaking CPU-based TEEs, we also show how extracted attestation keys can be used to compromise Nvidia's GPU Confidential Computing, allowing attackers to run AI workloads without any TEE protections. Finally, we examine the resilience of existing deployments to TEE compromises, showing how extracted attestation keys can potentially be used by attackers to extract millions of dollars of profit from various cryptocurrency and cloud compute services.

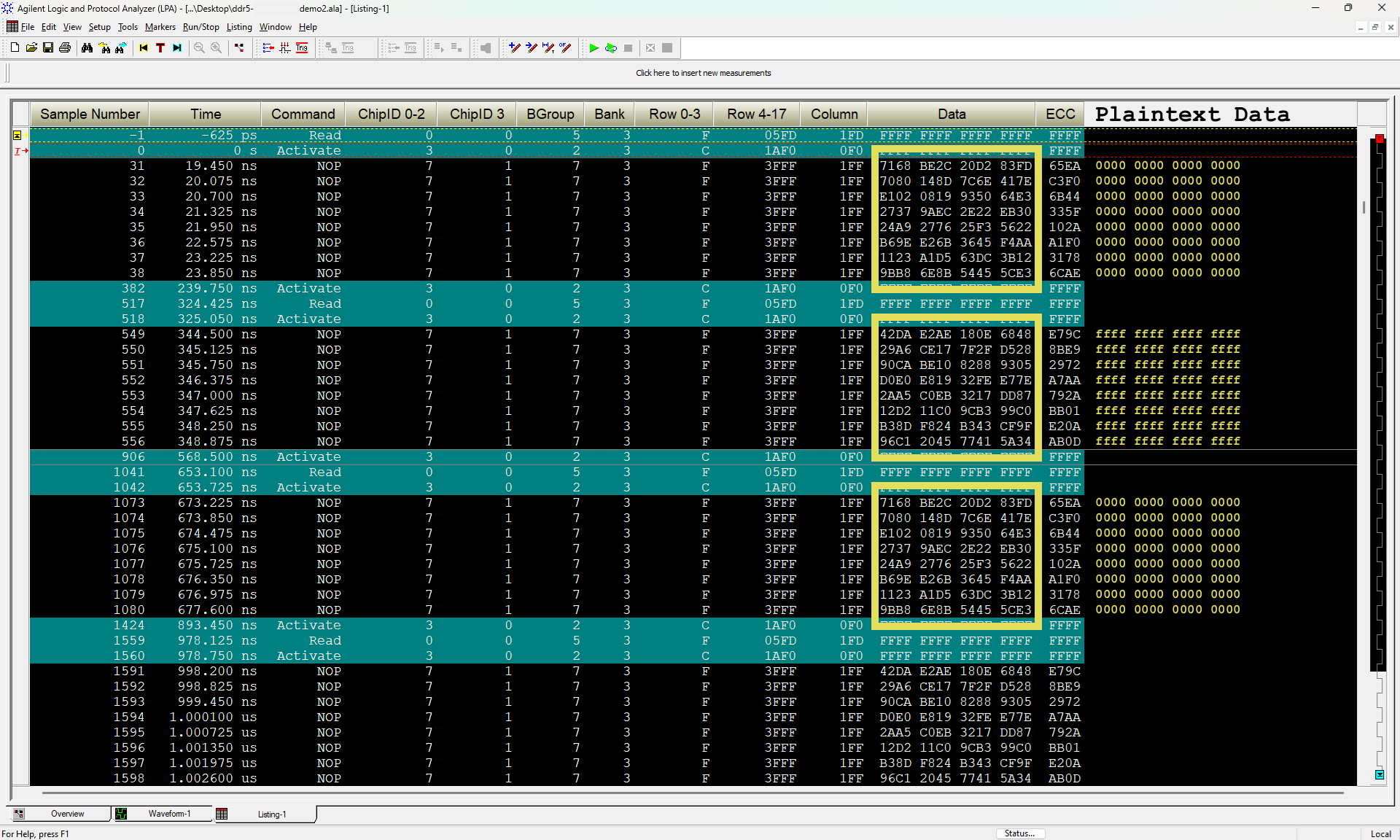

The DRAM Bus is the actual wiring and protocol that allows the processor to communicate with the DIMMs.

The DRAM Bus is the actual wiring and protocol that allows the processor to communicate with the DIMMs.